MRP: Hardres Court

Hardres Court

Editorial history

25/09/12, CSG: Created page

THIS ENTRY REQUIRES EDITING

Contents

Location and character

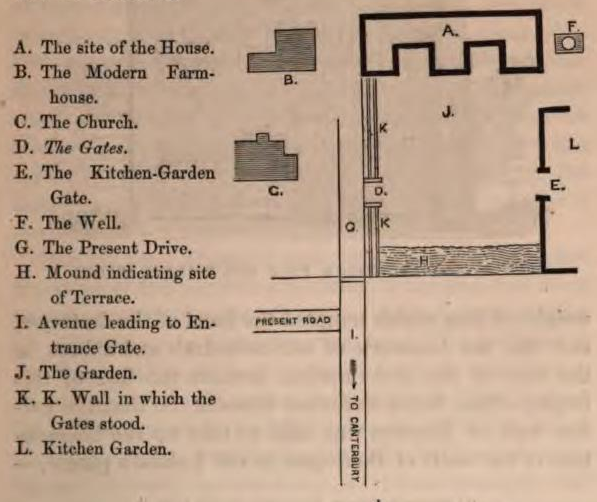

In 1800 Hardres Court was as a deserted building located on high ground away from any other inhabitation. The parish of Upper Hardres in which it stood was isolated, with a poor soil. Large areas of woodland remained. Just sixty years later, in 1861, the remains of Hardres Court were gone, and the landscape had been transformed through more intensive farming. The oak woods had been replaced by cornfields and hopgardens.

Wood engraving, Plan of Hardres Court, 1861

1800

The parish is a very lonely and unfrequented place, situated on high ground among the hills, having large tracts of woodland on each side of it. The Stonestreet way runs along the valley, near the western boundary of it; the soil of it is very poor, consisting mostly of either chalk, or a hungry red earth, covered with sharp slint stones. Hardres-court stands on high ground, a most retired and forlorn situation, and for some years past an almost deserted habitation; near it is the church and parsonage. There is no village, but at some distance further, near Stelling and the Minnis, there is a hamlet of cottages called Bossingham.[1]

1861

Cornfields and hop-gardens, unrelieved by a single tree, occupy the place of ancient woods of oak and other timber, once the most remarkable in their growth, and celebrated for their beauty in East Kent. The ancient manor-house with its quaint gardens and plantations, have given place to a farm-house with its homely accomplishments.[2]

Family pedigree

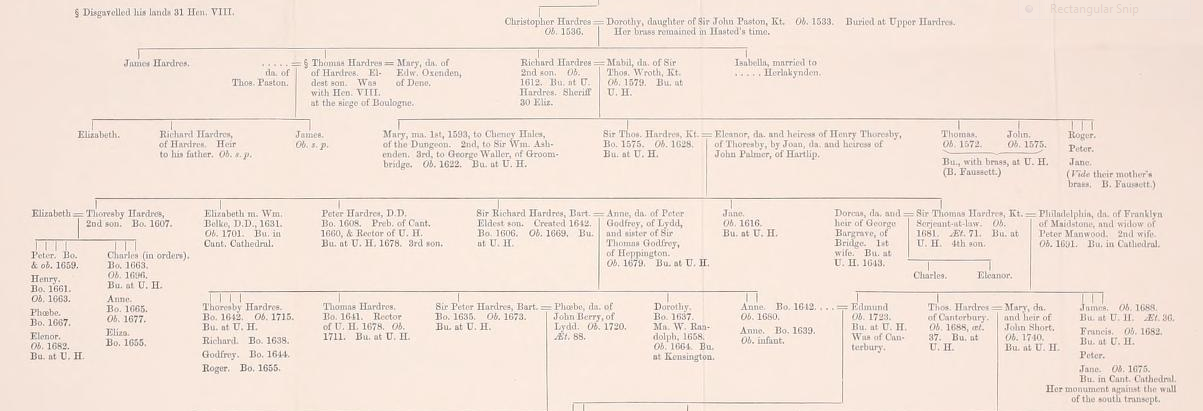

Hardres family pedigree was published in Archaelogia Cantiana, vol. 4 (London, 1858), opp. p. 57

Extract from Hardres Family Pedigree, 1858

Family background

Sir Richard Hardres' father, Sir Thomas Hardres (1575-1628), faced considerable financial difficulties, with a 1604 parliamentary act forcing the sale of Hardres lands to pay his creditors. Sir Thomas himself had fled overseas. His lands in which he was seized in fee or fee-tail were valued at £800 per annum. They were listed as the manors of Great Hardres (alt. Upper Hardres), Stelling and Bekehurst, with various messuages in Great Hardres, and further manors in Barden and Thoresby in the County of York, with messuages in Barden.[3]

Richard Hardres (1606-1669) married Anne Godfrey, daughter of Sir Peter Godfrey of Lydd, Kent before 1635. He was knighted in XXXX and raised to baronet in 1642. Sir Richard Hardres' brothers included Peter Hardres, D.D., (1608-1678), prebendary of Canterbury, and Sir Thomas Hardres (c.1610-1681), King's serjeant-at-law. His eldest son and heir was Sir Peter Hardres (1635-1673). [4]

Connection with Oxenden family

The Hardres name appears in the correspondence of both Henry Oxinden of Barham and of Sir George Oxenden.

Sir Richard Hardres (1606-1669) was related to the Oxenden and Master family through his marriage to Anne Godfrey, daughter of Peter Godfrey of Lydd, who was an acknowledged cousin of the Oxendens. Elizabeth Dallison, James Master, Michael Godrey, Sir George Oxenden and Sir Richard Hardres all write of their cousinship.

A sixteen or seventeen year old Richard Hardres wrote in 1622 to Richard Oxinden, Henry Oxinden of Barham's father, thanking him for use of a hawk.[5] Hardres Court, home of the Hardres family, was a few miles ot the north of Great Maydekin, Richard Oxinden's home, and subsequent home of Henry Oxinden of Barham.

Richard Oxinden's eldest son, Henry Oxinden of Barham, was on social terms with Richard Hardres (knighted in XXXX). In a letter to Sir Thomas Peyton Henry gave an account of his ride to Arundel with Colonel Richard Hardres and Lieutenant Colonel Oxinden to join the parliamentary forces, and the subsequent battle, at which another neighbour, Colonel Dixwell, was killed.[6]

Twenty years later, in early 1663, Sir Richard Hardres sent his son, Richard ("Dick") Hardres out to Surat to be under the care of Sir George Oxenden.

The young man, Dick Hardres, had given Elizabeth Dallison some considerable trouble. In September 1662 he had failed to board his intended ship out to Surat through carelessness. He had been due to sail with his cousins Streynsham Master and Henry Oxenden, together with Sir George Oxenden himself. Elizabeth, with considerable subsequent effort, procured passage for him on a later ship under the command of Captain Millett.

Nevertheless, Elizabeth trusted him sufficiently, as a cousin, to tell her brother that she had given Richard Hardres legal documents to carry out to Surat.[7] Cousin Richard had clearly learned his lesson. James Master, wrote to Sir George from Canterbury a couple of days after Elizabeth. He reported: "Coz:n Rich:d Hardresse came to Towne deasigndd then for Deale & was very earnest for all y:e papers & lres belonging to you, & though I used many arguments y:t y:e Ship Could not bee then in y:e Downes, the Burnt Child did dread the fire, & hee would not beleeve, but goo & see..."[8] Sir Richard Hardres himself wrote a letter of thanks and apology on behalf of his contrite son to go out with Elizabeth and James' letters and documents. His son had missed his first voyage "through his own neglect" and subsequently has endeavoured "with much Contrition & promises of a future & better Care & dilligence" to be of service. Sir George appears to have had a soft spot for the errant relation as Sir Richard Hardres notes, finding that Sir George always had "A more speciall affection for him than Ordinary, w:ch hee & I are ever bound to acknowledge." Sir Richard, who betrays some signs of exasperation with his son, asked for Sir George to guide his son, but did not desire or expect favours inappropriate to his son's absence of experience. His hope for his son was that "hee cann make but a younger Brothers substistance", his friends and his father having done all they can for him.[9]

Correspondence

October 3rd, 1622

"HONORED COSIN,

I am much indebted to you for lettinge your man bringe ouer the hawke unto mee, whome we got to call her loose but were like not to see her againe that night, for the hawke is not in case to flie, neither will shee be in his keepinge, wherefore if it please you to leave her with mee fowre or five days my man shall make her comming, and then I will give you as much money for her as any man, soe with my service remembred unto yourselfe and your vertuous mother I rest

Your assured lovinge kinsman

To command

RI: HARDRES"[10]

Potential primary sources

Potential secondary sources

- ↑ Edward Hasted, 'Parishes: Upper Hardres', The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: vol 9 (1800), pp. 304-309. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63568 Date accessed: 26 September 2011

- ↑ Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 4 (London, 1861), p. 43

- ↑ Archaeologia Cantiana, vol. 4 (London, 1861), pp. 53-54

- ↑ 'Hardres family pedigree' in Archaelogia Cantiana, vol. 4 (London, 1858), opp. p. 57; Edward Hasted, 'Parishes: Upper Hardres', The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: vol 9 (1800), pp. 304-309. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=63568 Date accessed: 26 September 2011

- ↑ BL, MS. XXXXXX, Letter from Richard Hardres to Richard Oxinden (of Barham), Hardres Court, October 3rd, 1622. See Letter from Sir Richard Hardres to Richard Oxinden

- ↑ BL, MS. 28,000, f. 303, Letter from Henry Oxinden to Sir Thomas Peyton, February 6th 1643/44

- ↑ BL, Letter from Elizabeth Dallison to Sir George Oxenden, April 3rd 1663, ff. 84-86. See 3rd April 1663, Letter from Elizabeth Dalyson to Sir GO, London

- ↑ BL, Letter from James Master to Sir George Oxenden, April 6th 1663, ff. 102-104. See 6th April 1663, Letter from James Master to Sir GO, Canterbury

- ↑ BL, Letter from Sir Richard Hardres to Sir George Oxenden, April ?7th 1663, ff. ?-?. See 7th April 1663, Letter from Richard Hardres to Sir GO, Hardres Court

- ↑ BL, MS. XXXXXX, Letter from Richard Hardres to Richard Oxinden (of Barham), Hardres Court, October 3rd, 1622. See Letter from Sir Richard Hardres to Richard Oxinden

- ↑ http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12275, viewed 24/12/11